Lumen R4A Long-Term Capital Market Assumptions

While planning for a CMA (Capital Market Assumptions) at the close of the year—and in the wake of an unexpected U.S. election result—it’s tempting to adopt a short-term perspective, focusing on the uncertainties and anxieties generated by President-elect Trump’s policies and their potentially disruptive impact on the economy and the market.

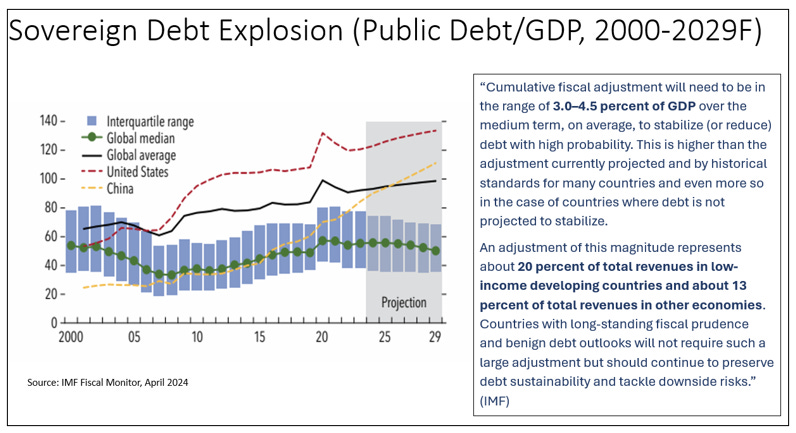

However, even the most egregious measures proposed by Trump simply accelerate a relentless underlying trend that started well before him, or deliberate fiscal profligacy paired with unrestrained money creation to spur growth at all costs. Whatever one thinks of Trump’s announced measures, they all ultimately have a sizeable fiscal and inflation cost. In other words, while most are consumed with tariffs and trade wars (the tree), the Forest (sovereign debt accumulation) is burning.

Indeed, the relentless ditching of sound macro policies initiated well before Trump will continue to stoke inflation—particularly in the cost of necessities like food—and exacerbate income inequality, which in turn fuels political discomfort and rampant populism, all tapered off with (one can only guess) … more fiscal largesse, wicked effects on sovereign yields, stoking uncertainties, widening risk premia across the capital structure, and ultimately undermining valuations.

Add to that structural headwind to growth – a combination of demographics, climate change, fragmentation (or de-globalization) amongst others – undermining topline and earnings and there is good reason to expect that market returns – driven by valuation plus earnings – will be lower than long term averages enjoyed over the past several decades.

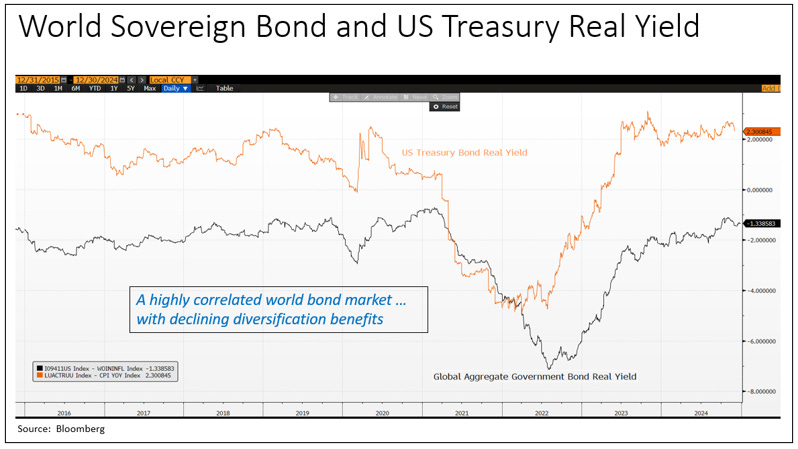

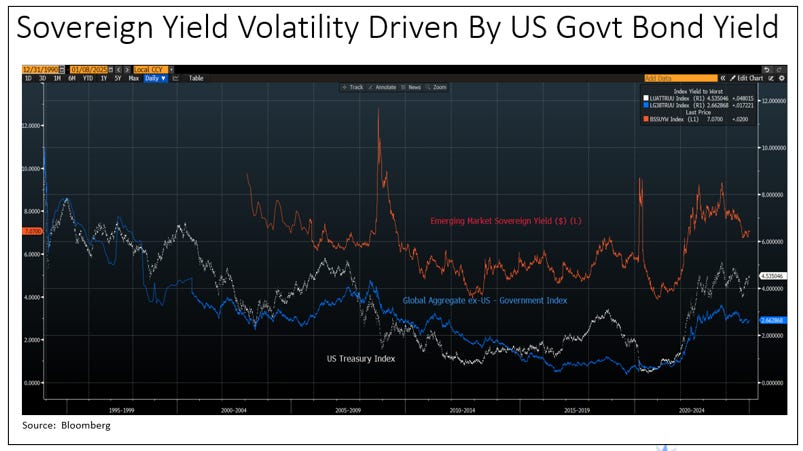

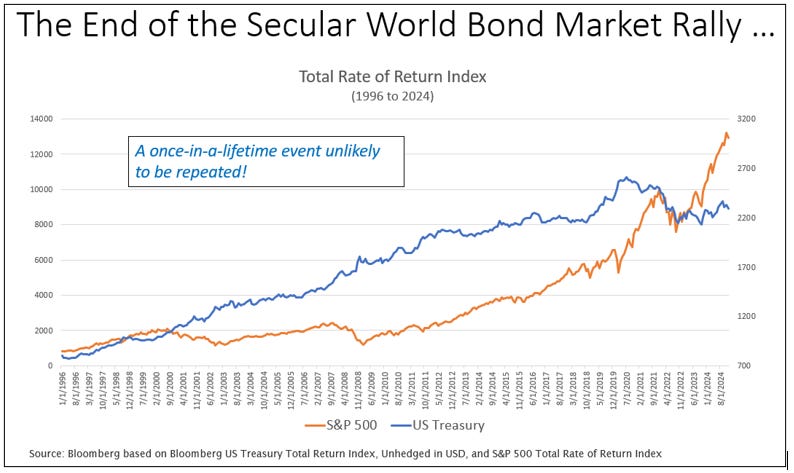

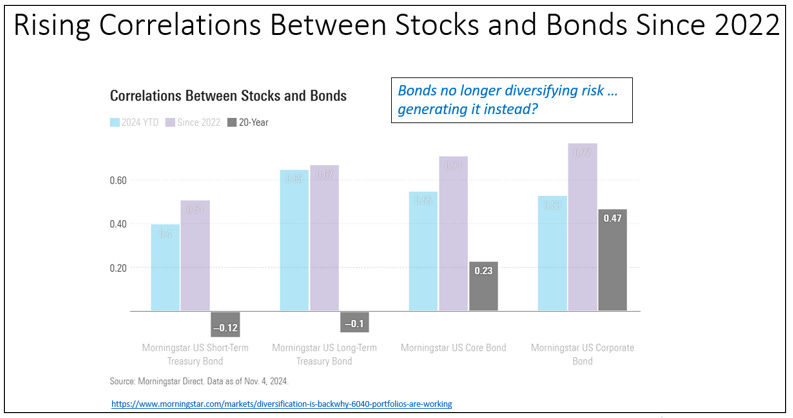

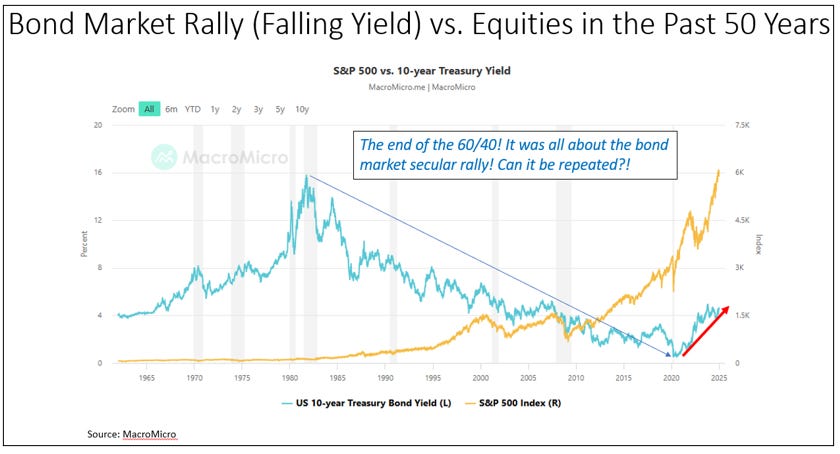

In particular, the “new” structural disruptive element for asset allocators is that fixed income can no longer be relied upon as a risk diversifier and source of income (courtesy of the biggest, once-in-a-lifetime rally over the last 50 years). Accordingly, this is making the old 60/40 approach and its variation obsolete and outright volatile. Asset allocation will have to be a lot more selective, dynamic, and active, a stark departure from the widespread passive or one-size-fits-all approach!

The Forest

The roots of unorthodox policies can be traced back to the late 1990s, when the U.S. Federal Reserve under Chairman Alan Greenspan (the “Maestro”) took the unprecedented step of intervening—on a massive scale of roughly $5 billion—to rescue a private fund, Long-Term Capital Management, managed by John Meriwether [1].

This intervention effectively set the stage and provided a blueprint for future bailouts and the “whatever it takes” approach. When the subprime mortgage fiasco erupted into a global crisis, central banks worldwide were quick to flood markets with cheap money (ZIRP), expanding their balance sheets to unprecedented levels. The pandemic then opened the floodgates further.

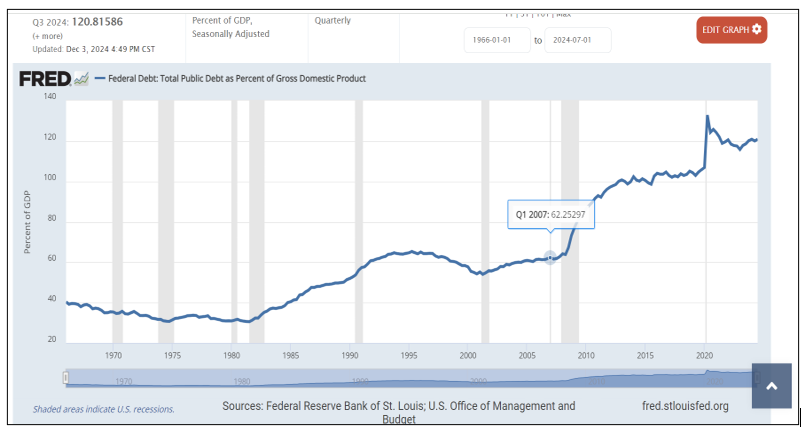

While most economists were busy criticizing these irresponsible monetary policies, fiscal authorities were simultaneously running ever-larger deficits, causing public debt to balloon. The U.S. public debt story offers a prime example of this explosive trend.

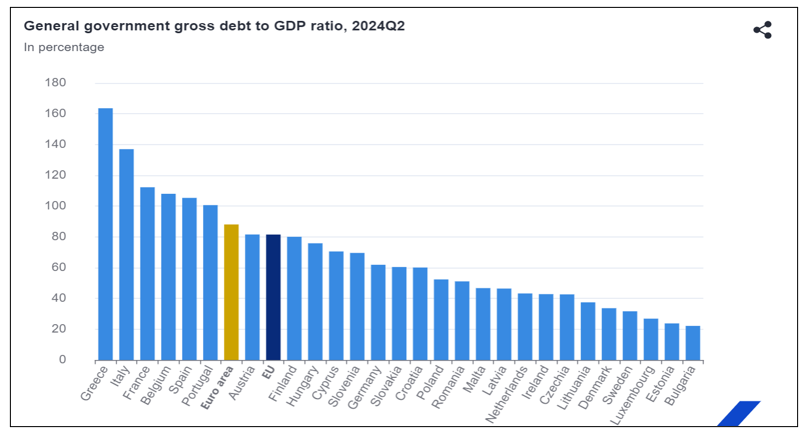

Ditto for the European Union, where the added “challenges” to the debt ratio are structural impediments to growth such as demographics, low productivity, and energy amongst others.

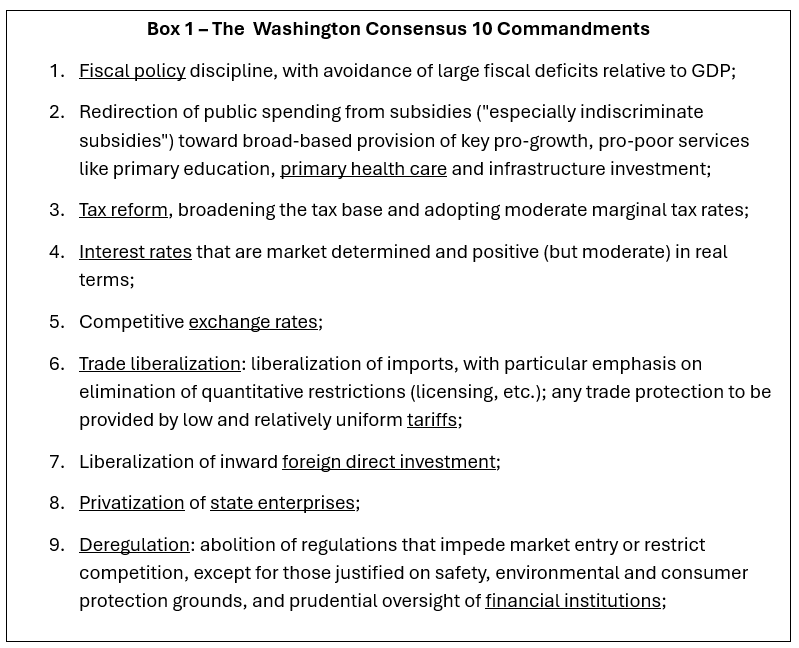

In other words, the Washington Consensus and its “ten commandments” (see Box)—or the liberal economic precepts that guided policymakers, fostered the Great Moderation, and generated immense global wealth—are effectively gone. Ironically, they have been dismantled by the very authorities who once championed them (IMF, Federal Reserve, etc. The dilemma is: what will guide sound macro policies and appease market anxiety (and alleviate the coming structural pressure on risk premium) at this point is anybody’s guess.

And of course, there is a “Trump trade”—but it is crucial to remember that this is just that: a trade. It involves buying low and selling high, whatever “low” and “high” might mean now and ever. This is not to be confused with true investment, which involves purchasing and keeping assets that reliably generate stable future cash flows. A true investment requires a fundamentally distinct set of (valuations plus earnings) considerations based on reliably sound macro policies.

The Tree

As estimated already, Trump’s policies and measures are expected to add $7.7 trillion to U.S. public debt and counting! Given these numbers and the size of the (already) massive amount of outstanding debt, it may be pure dreaming to rely on trickle-down economics and hope for higher growth rates or to trust in “tough” politicians or “special” personalities to avoid a coming public debt reckoning.

For example, Elon Musk’s claim that he could bring the budget deficit down to zero seems more like alchemy than strategy. He might excel at complex calculations but could be overlooking basic arithmetic. As it were, 87% of the U.S. budget is already earmarked or tied to programs that Trump pledged not to touch (defense, interest on the debt, and Social Security). Musk would therefore need to find $2 trillion in cuts out of the remaining $910 billion of discretionary spending … good luck, Elon!

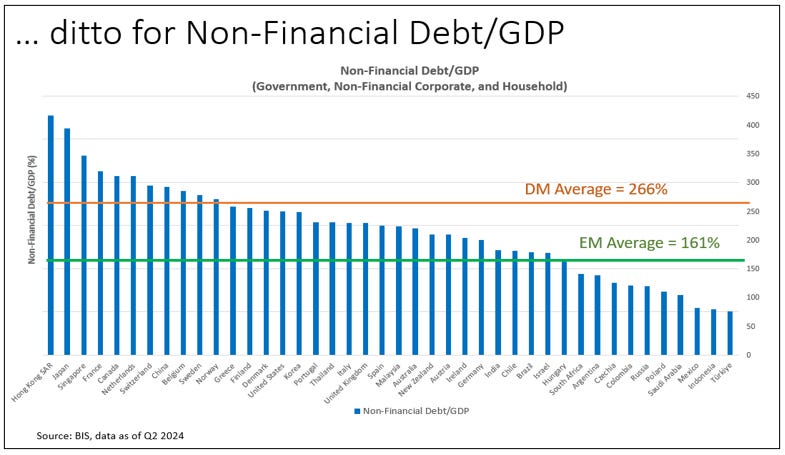

And the debt situation is no better in the rest of the world … in fact, it may be worse.

Consider the European Union: the rigidity of member states’ budgets and the difficulty of closing sizable deficits or reducing debt levels are well known, pushing them far from the Maastricht criteria standards. One can attribute this to numerous factors—weak growth, unfavorable demographics, generous and costly social safety nets, persistently fragmented markets, and a shortage of technological innovation and productivity (as highlighted in Draghi’s report).

Indeed, and according to some interpretations of the Draghi Report, Europe could be on a path of Japanification … which invariably leads to a lot more debt. Regardless of the cause, Europe continues to rely heavily on fiscal policy, adding to its already substantial debt load. Paradoxically, the blame for Germany’s current growth dilemma is that various administrations there have not used the fiscal/debt option enough!

With primary surpluses impossible given the current political (and geopolitical) climate in major EU members, and growth lagging behind interest rates, the debt problem only continues to worsen. Indeed, rather than moving toward correction, the situation is deteriorating. For example, one immediate “Trump effect” is the EU’s recent, unprecedented agreement to raise at least €500 billion for an EU-wide defense fund—a figure that official sources acknowledge may be a conservative estimate.

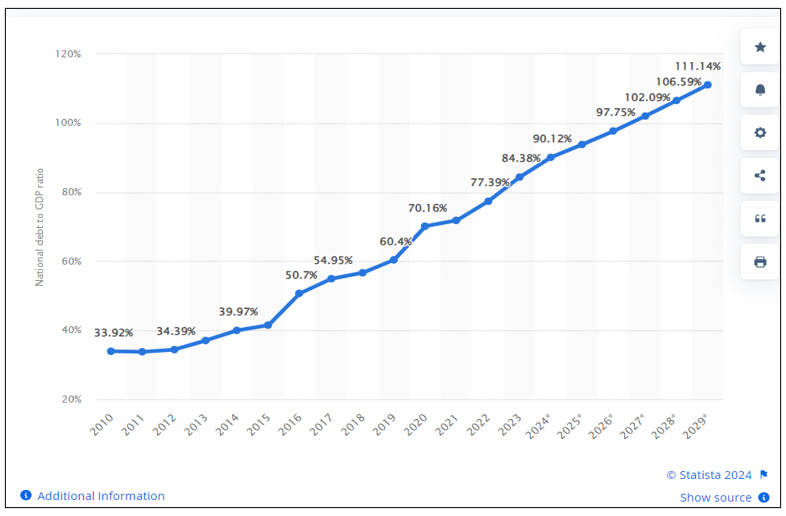

The situation in China, the third biggest pole of the world economy, is also not different, with the pile of public debt just ballooning:

National debt in relation to gross domestic product (GDP) in China from 2010 to 2023 with forecasts until 2029

The need to change the growth engine – i.e., over-investment and exports – that lifted millions of Chinese citizens out of poverty is widely acknowledged. However, the challenge lies in “shifting gears” without adding further to an already massive debt burden—public and private debts now approach nearly three times the nation’s GDP (see Appendix). Yet, in response to well-known structural issues (such as real estate imbalances, youth unemployment, demographic challenges, sluggish growth, and deflation), the authorities’ preferred tool remains, once again … the fiscal lever!

In other words, and in conclusion, despite promises of a change of course by all administrations, the pile of debt continues to grow. The trouble is that the old assumption that the supply and level of public debt do not matter if governments are considered safe bets is about to be tested, and the stability and reliability of sovereign yields with it, Trump or no Trump!

Supply did not matter when debt levels relative to GDP were manageable … no longer the case. As the world grapples with lackluster growth and political constraints courtesy of the wave of blind populism, the delicate balance between interest rates, growth, and fiscal policy becomes harder to maintain.

Without structural reforms, credible fiscal plans, or a return to robust growth, there’s a real risk of entering a vicious cycle: higher debt leads to concerns over sustainability, which puts upward pressure on borrowing costs, which – given the sizeable supply – in turn exacerbates debt servicing and accumulation, reinforcing investor skepticism, and leading to even higher yields. Governments may find they must adopt credible long-term fiscal strategies or else face an environment where public debt supply does matter—and quite a lot.

The implicit deduction is that, at the bare minimum, growth can no longer be “engineered” by relying on more debt, on the contrary. In practical terms, the choice will be either low growth or higher sovereign yields, again, Trump or no Trump. The real danger is ending up with both amidst yet another crisis of global reach, e.g., pandemics, subprime, etc.

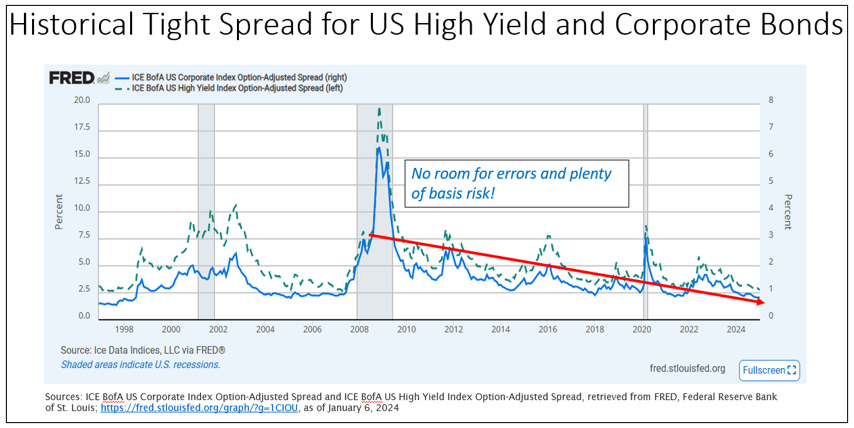

Given this vulnerable backdrop for the “risk-free” segment of the capital structure, it’s rather surprising that markets seem to be shrugging it off, overtaken by euphoria about a new “Goldilocks”[2] scenario—good growth and no inflation … that is focusing on the tree. Indeed, despite the brewing debt pressure in much of the world, long-term yields continue to price in an exceptionally optimistic view of future growth and inflation, and, by construction, the trend returns in risky assets!

Our sense is that this widespread optimism about sovereign yields may stem from a simple and typical mean-reversion trading bias. In other words, investors (traders?) seem to be treating the past secular bond market rally—which pushed sovereign yields down from 16–18% in the 1980s to near-zero or even negative territory in recent years—as the norm rather than the extraordinary, once-in-a-lifetime event it truly was (see Appendix).

In theory, long-term yields should be determined by trend growth, trend inflation, and a term premium. We are far from that scenario. In the U.S. Treasury market—effectively the world benchmark—yields at ~4.5% remain well below these fundamental determinants, and market expectations point to further declines.

The situation elsewhere is not vastly different. Yields in Japan and China hover around 1% and 2% respectively, while in Europe they remain significantly lower than those in the U.S. Even Italy and Greece, both burdened with debt-to-GDP ratios well above 140% and rising, are trading about one percentage point below the 10-year U.S. Treasury. It is only when we turn to certain emerging markets that we find yields more closely aligned with underlying risks, albeit selectively and with plenty of caveats!

Conclusion

Unorthodox policies leading to the dismantling of the liberal economic precepts that guided the world through a prolonged period of economic goldilocks will at the bare minimum generate anxiety and uncertainties, leading to more volatility and risk perception, thus pressuring risk premia up across all asset classes. The tipping point for an outright crisis may very well be the realization that the public debt burden is becoming unsustainable and activates the bond vigilantes, bringing the US 10-year yield (or the global benchmark) well above 5 percent, potentially initiating a structural bear market in fixed income!

Asset Allocation

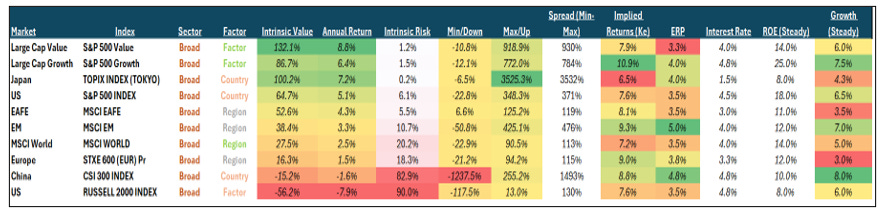

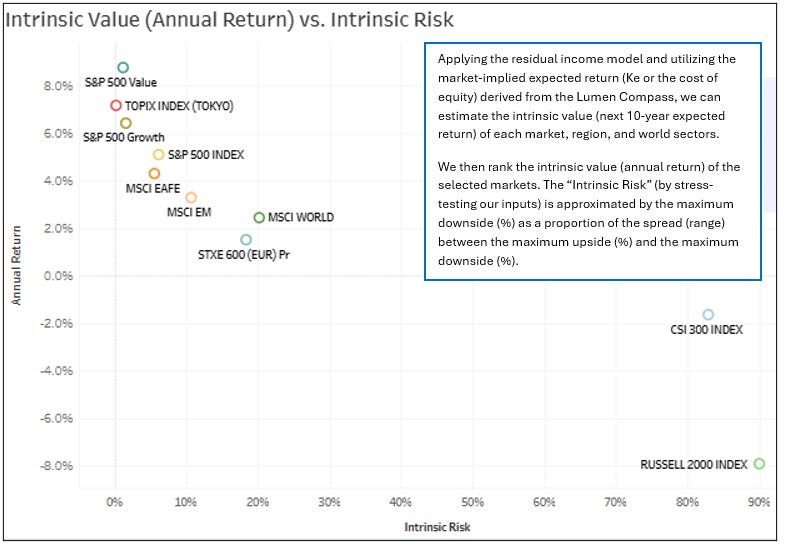

When devising CMAs, we follow (and apply) a simple but powerful precept: market returns, especially over the long term, are driven by valuations and earnings. In turn, valuations are influenced by yields (or the time value of money) and risk premiums, while earnings depend on top-line growth and profit margins. Given this framework, it’s clear why we anticipate returns significantly below long-term trends across the board:

- Sovereign yields are likely to become more volatile and move upward, reflecting heightened risk perceptions and a pull toward a “neutral” level. Indeed, we could be on the cusp of a structural bear market in fixed income.

- Risk premiums are expected to rise, driven by the uncertainties and volatility stemming from unorthodox policies and the erosion of the liberal economic principles that underpinned a prolonged period of economic stability and provided necessary market guidance.

- Top-line growth worldwide will remain below recent historical averages, hindered by structural headwinds such as unfavorable demographics, climate change, and the fragmentation of global trade. These challenges will then be further exacerbated by necessary restrictive policy environments worldwide.

- Profit margins may offer a rare bright spot, albeit for selective sectors and potentially benefiting from technological advancements. However, margins will remain susceptible to the pressures of higher funding costs and persistent inflation.

Accordingly:

- Given the current risks, traditional asset allocation strategies that rely on stability and diversification attributes of fixed income are likely to underperform. The classic 60/40 portfolio model (60% equities and 40% bonds), along with its variations, has already proven disappointing and increasingly risky. Notably, it has incurred significant losses from the fixed income component in two of the past three years, challenging its reputation as a balanced and reliable approach to investment.

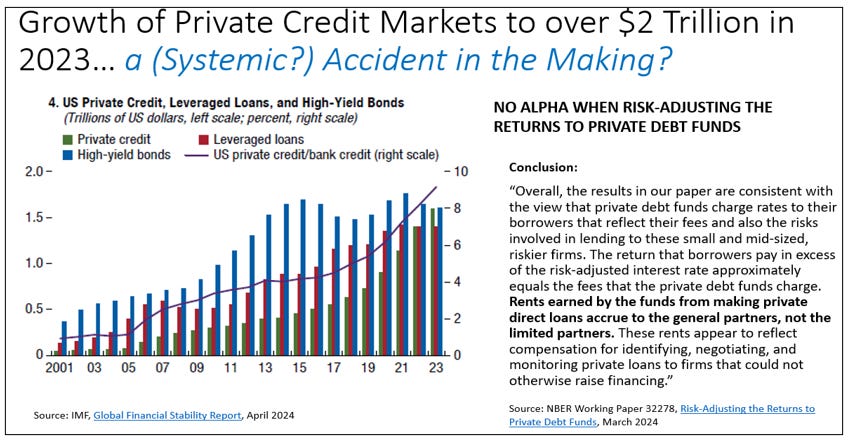

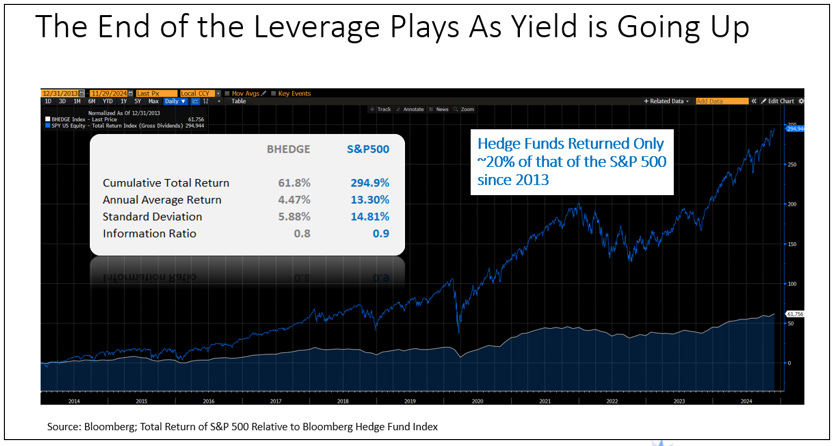

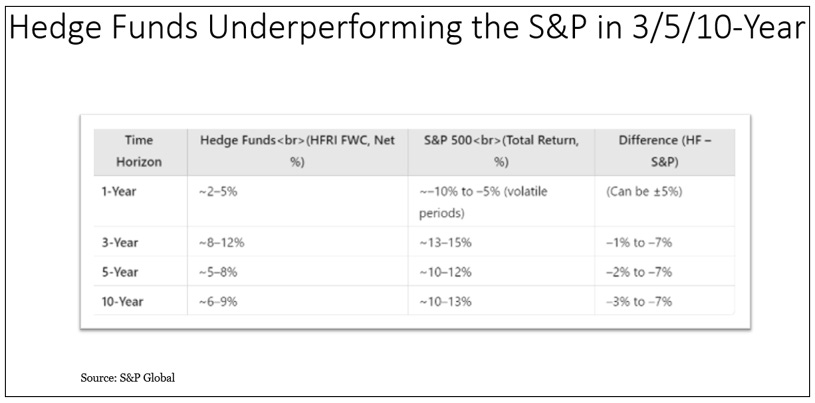

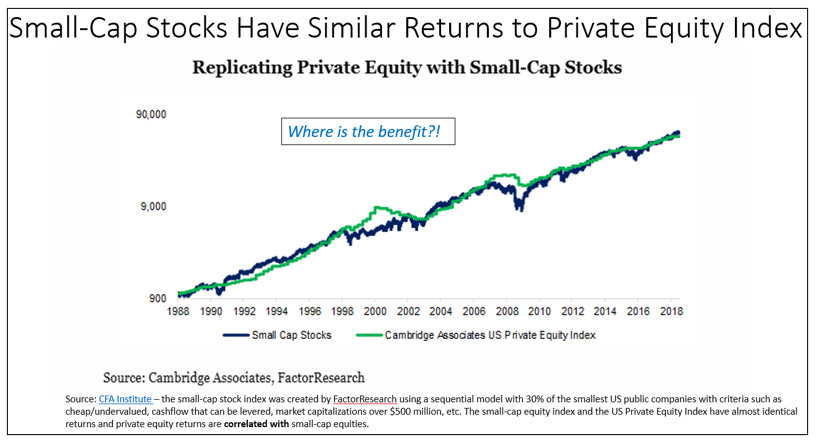

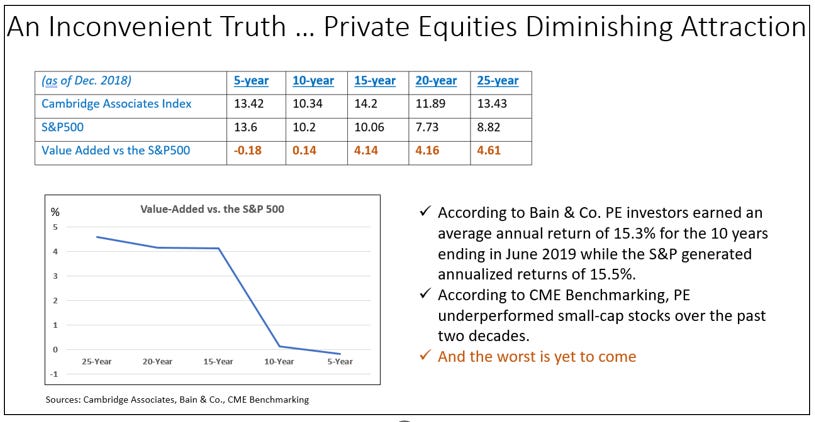

- Ditto for all those strategies that benefited tremendously (only?) from historically low yields and leverage, e.g., LBOs, Real Estate, and Hedge funds.

- We believe the entire fixed income market represents the most vulnerable segment of the capital structure, facing mounting pressures from sizeable basis risk, tight credit spreads in both investment-grade and high-yield debt, and a challenging environment of subdued top-line growth.

o The most acute risks, however, are concentrated in the private credit market, which has become a hotspot for excessive risk-taking. Practices such as loose or absent covenants, Payment-In-Kind (PIK) arrangements, and questionable liquidity are alarmingly prevalent, evoking parallels to the excesses that have historically foreshadowed financial crises.

o Thus, we recommend a very defensive allocation to fixed income: TIPS: To protect against inflation; Short to mid-term maturity: To reduce sensitivity to rising interest rates; floating Rate Notes (FRNs): to take advantage of rising rates; High-Quality Corporate Bonds: to capture higher yields from strong companies; Global Safe-haven bonds: for diversification.

- Paradoxically, equity (or the riskiest part of the cap structure) may offer much better opportunities not just for returns but also for risk reduction via active diversification; this, however, very selectively across different markets (the US versus the rest of the world), sectors (tech, industrials, defensive), and factors (value, quality, and dividend).

o Some sectors (and countries) will benefit directly and earlier from technology, particularly AI: Information Technology via direct innovation driver; Healthcare via transformational applications; Communication Services via connectivity enhancements; Industrials via efficiency gains through automation and robotics.

- Accordingly, passive investment strategies tied to major aggregate benchmarks (e.g., S&P 500, Euro Stoxx 600, MSCI World) may no longer deliver the competitive returns seen in recent years. The increasingly challenging outlook for market return calls for more targeted and thematic investment approaches to navigate emerging challenges and opportunities effectively.

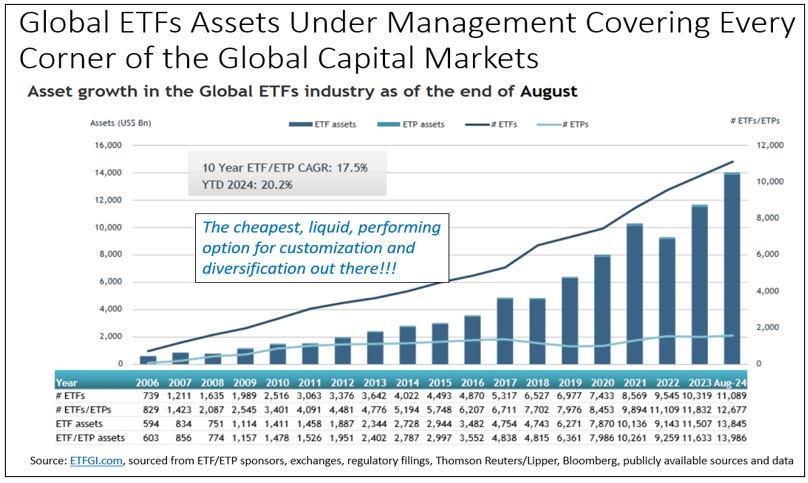

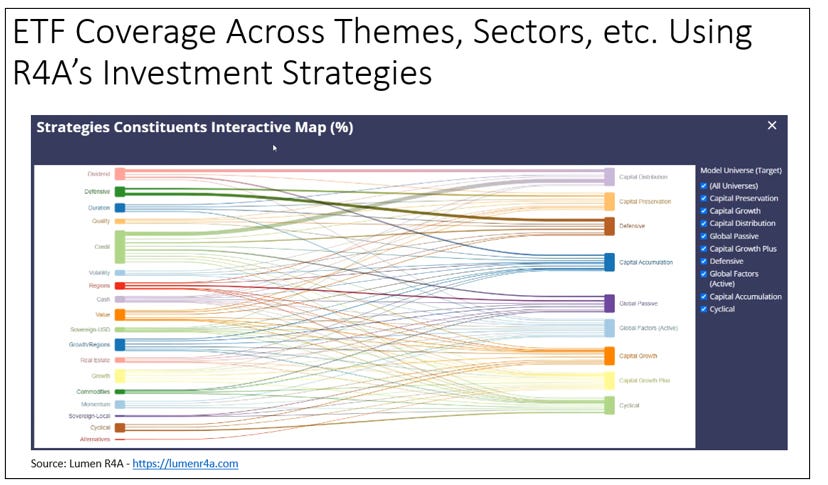

- Given the prospect of lower returns compared to historical norms, not to mention the risk potential, we recommend an active and dynamic diversification strategy, in any case, the best, cheapest, and most effective risk management method. We recommend taking full advantage of the extensive range of ETFs—spanning tens of thousands of options—that cover every segment of the global capital markets, sectors, investment styles, themes, and factors.

o To be sure, ETFs provide superior diversification, risk management, and better relative performance at a significantly lower cost compared to alternative assets, in addition to much better liquidity and ease of execution. In contrast, and contrary to common belief and practice, the diversification benefits and the relative performance of alternative assets have often fallen short, particularly during periods of market turbulence, when they are needed most (see Appendix).

For more specific individual projections, please see our the following tables, charts and long-term projections across major markets, benchmarks, and sectors using our proprietary tools and Residual Income Model methodology in the Appendix.

Visit Lumen R4A (https://lumenr4a.com) to learn more about R4A and our approach.

December 2024

San Francisco

[1] Some argue that the trend of monetary authorities intervening in support of the market started during the stock market crash of 1987 leading to the famous “Greenspan Put”.

[2] A Goldilocks economy is not too hot or too cold but just right, to steal a line from the popular children’s story “Goldilocks and the Three Bears”. The term describes an ideal state for an economic system. There’s full employment, economic stability, and stable growth in this perfect state.

Appendix

Explore Lumen R4A for global asset allocation and portfolio construction with our state-of-the-art industry tools.

Please leave a comment or get in touch with us if you have any questions.

Download a PDF of the report here.

Disclaimer: The content is for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, tax, investment, financial or other advice. Nothing here constitutes a solicitation, recommendation, or offer to buy or sell any securities or financial instruments. Consult with your financial advisor before making any investment or financial decisions.